Gabrielle Bates

Notes on Spirals

“[The imaginary] works in a spiral: from one circularity to the next . . . The imaginary becomes complete on the margins of every new linear projection.”

—Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing

“Around the poem about to be made, the precious vortex: the ego, the id, the world. And the most extraordinary contacts: all the pasts, all the futures . . . All the flux, all the rays . . . Everything has a right to live. Everything is summoned. Everything awaits.”

—Aimé Césaire, “Poetry and Knowledge,” trans. A. James Arnold

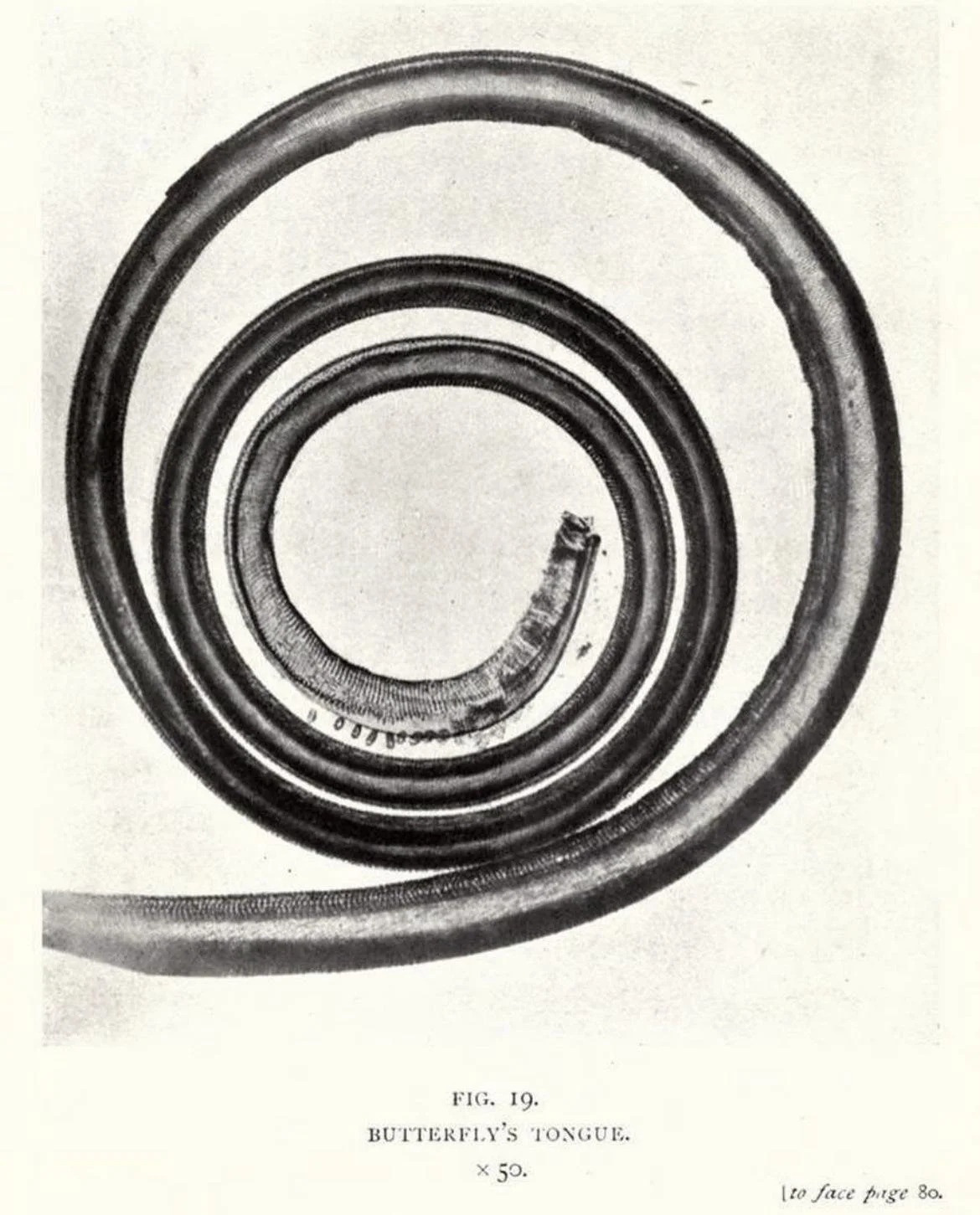

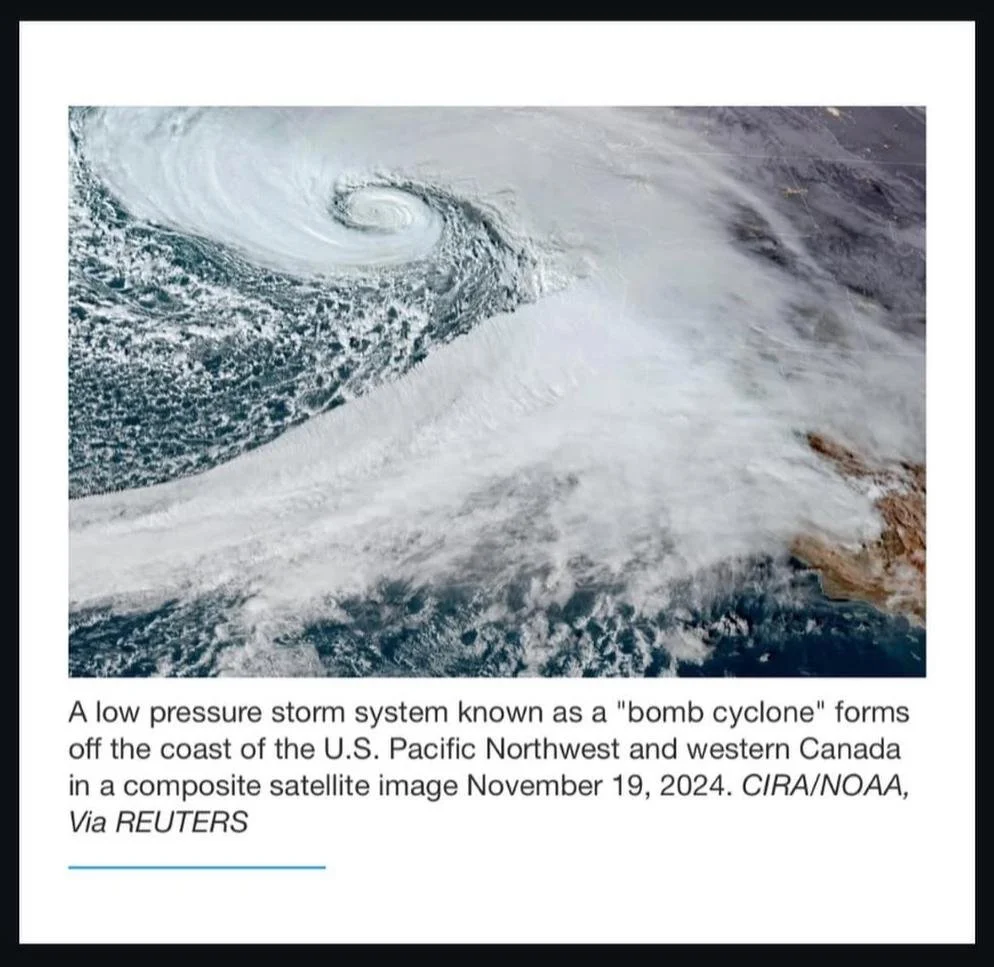

[Image citation: Butterfly Tongue, Public Domain; REUTERS]

Last November in Portland, for the Tin House Writers’ Conference, I gave a talk celebrating the spiral—as structure, as spirit—turning to various images and three exemplary, contrastive poems to illustrate various ways we might, as poets on the page, subvert a straightness of thought and collaborate with both mystery and constraint to approach crucial, compelling unknowns.

Now, as then, I invite you to draw a spiral, as tightly as you can.

My personal interest in the spiral as a poetic structure is related to my interest in collaborations between organic and received form. By organic form I mean the approach described by Denise Levertov in “Some Notes on Organic Form,” wherein the poet listens actively to writing as it emerges, sensing, with a mystical organ, the body of form, as a whole, the poem is seeking as “revelation of its content.” Received form, by contrast, a poet brings to drafts from far away, imposing upon utterance an array of conventions, socio-historically determined.

While I do enjoy thinking about received forms, and some of my favorite poets make revelatory use of them (Dujie Tahat, with the ghazal; Emily Dickinson, with hymn), in my own practice, the use of received form has always felt largely hollow and frivolous—counter, at times, to why I write poems at all. For this reason, I’ve tended to place myself in the camp of the organic formalists, rooted in my belief that form is somewhat inherent to utterance, something a poet can ascertain and nurture with perception, by humbling oneself before language as it emerges, noting where language seems to want to go, and how. How does the energy flare or dim in response to certain choices? By what rhythm does this instigating burst of speech seem to want to move? What kind of unseen, unknown tree would drop this particular fruit?*

While I’ve largely embraced these mystical processes and questions of organic form, I must confess to having a literal side that feels somewhat bereft before it, and a side too that wants for the occasional fence to press against, that understands the creative value of additional parameters. Because of this, I am increasingly allured by forms that feel fundamentally organic, but that collaborate also, in some way, with the imposition of a set pattern, applying a generative constraint adapted from the principles of a spontaneously emerged utterance or other naturally occurring phenomena.

A breed of nonce form, like Marianne Moore’s syllabics, comes to mind as an example. To determine the syllable counts of each line in her stanzas, Moore did not pick a series of numbers at random, but attended rather to how the language started to emerge; she used the syllable count and visual arrangement of the first stanza as a blueprint for the ones to follow.** The “words cluster like chromosomes,” she says. Of this process, she is “governed by the pull of the sentence as the pull of a fabric is governed by gravity.”

*This sentence echoes Paul Valéry’s metaphor about “first lines” in poems, as relayed by Mary Ruefle in Madness, Rack, and Honey

**Marianne Moore, The Paris Review, Art of Poetry, No. 4, 1961

As I reread those similes, I realize that DNA and gravity are likely the primary underlying metaphors for much thinking on the spiral in relation to poetry: DNA on the up-close, zoomed-in scale, and gravity—particularly the spiralling trajectory of objects when pulled towards the engulfment of a black hole—in the cosmic, zoomed-out scale. For those of us who regard poems to a degree as living organisms, approaching poems as beings that course with energy, respond to stimuli, and are mutable in power and function, it follows that, as the body of any other, the poem’s body would grow from the directives of its helixes, which we might, with curiosity and care, coax forth, amass, and activate.

[Image citations: ResearchGate; Galileo Unbound (edited)]

Furthermore, that human beings have been compelled by the spiral, incorporating it into their sacred architectures and artworks for as far back as we have record, gives me, as a poet invested in both the primal and the sacred, a meaningful talisman—a form received, not as a series of conventions from offshoots of human sociality, but from organic forces that act on, around, and within the human and the nonhuman both.

We hear so often Emily Dickinson’s charge to “Tell all the truth but tell it slant

. . . ” What is a spiral, ultimately, but the trajectory of utmost slantness, moving towards or away from something core?

* * *

We will travel now through three poems, noting how “the spiral” is at work. Beginning here with the shortest, most literal example:

“The Last Anchoress,” by Patrycja Humienik, from her debut collection We Contain Landscapes (Tin House, 2025), is a concrete or visual poem that takes the shape of a spiral on the page. In this way it is an obvious example for the topic at hand, but there are other, more subtle ways the spiral is functioning here as well.

An anchoress is a woman, typically Catholic, who lives alone in a cell attached to a church. Nazarena, specifically, was an American Roman Catholic who spent most of her life in a monastery until she died in 1990. We can immediately feel in this poem, experiencing the overall shape and its title alone, a resonant pairing of content and form. Anyone who’s ever climbed cupola stairs might feel the echo of that trajectory, up up up or down down down its coil. We experience, as we read the poem, a sense of inwardness, perhaps even a creeping claustrophobia, as the circle tightens. Furthermore, to read the poem requires us to literally turn the page in circles, slowing down the pace at which we can read, inducing perhaps a degree of dizziness. Like water circling a drain, the circling of the language here gradually quickens in pace. In general, the sentence units in this poem get shorter as the poem progresses, enacting via syntax, in a subtle but palpable way, the poem’s ongoing contraction. The speaker’s relationship to herself also changes as the spiral closes in on its core. In the first two sentences, the speaker is not present in the language at all. Then, at the very end of the third sentence, she appears: The “Here I am” feels like a rupture, a full arrival, the self accepting and admitting—encountering, maybe—herself at that interior curve. As she approaches the inmost point, the deferral (denial?) of an “I” ends. And yet, in this moment of self-encounter, the lens of the poem also widely and wildly expands, placing something giant and unruly (the ocean) inside of the small stone cell. There’s panic (“Stroke, float, terror”); a stripped-down, honest self-reckoning (“I prayed for this. I didn’t have to.”); and then what we could call the poem’s epiphany, regarding a paradox of touch, wherein the sentence unit expands again, refuting the expectation of utmost contraction, making the end, and the insides of the self, ultimately, expand.

This second poem example is the opening excerpt from a book-length poem by Inger Christensen, called Alphabet, translated from the Danish by Susanna Nied.

Here are the first five sections:

1

apricot trees exist, apricot trees exist

2

bracken exists; and blackberries, blackberries

bromine exists; and hydrogen, hydrogen

3

cicadas exist; chicory, chromium,

citrus trees; cicadas exist;

cicadas, cedars, cypresses, the cerebellum

4

doves exist, dreamers, and dolls;

killers exist, and doves, and doves;

haze, dioxin, and days; days

exist, days and death; and poems

exist; poems, days, death

5

early fall exists; aftertaste, afterthought;

seclusion and angels exist;

widows and elk exist; every

detail exists; memory, memory’s light;

afterglow exists; oaks, elms,

junipers, sameness, loneliness exist;

eider ducks, spiders, and vinegar

exist, and the future, the future

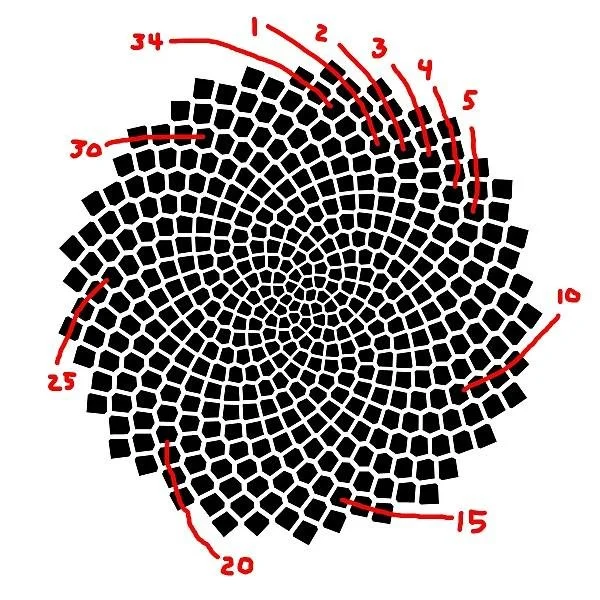

If Humienik’s “The Last Anchoress” moves us in a short, literal, inward spiral on the page, Christensen’s Alphabet evokes through its form a long spiral outward, spreading and engulfing more terrain as it goes on. The number of lines in each section of Alphabet is determined by what is commonly known as the Fibonacci sequence, a series of numbers first described in Indian mathematics, some 1000 years before Fibonacci was born, by Acharya Pingala, who placed them in relation to patterns in Sanskrit poetry. The sequence, in which each number is the sum of the two numbers before it (proceeding 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21. . .), is a naturally occurring mathematical phenomenon, often charted as a spiral, which has been noted—with exactness, or in very close echo—in sunflower seeds, snail shells, pine cones, snake coils, hurricanes, galaxies, gastropod fossils, fern fiddle-heads, pineapple spikes, pea plant tendrils, fingertip whorls, ram horns, mollusc shells, the flight-path a hawk takes down to its prey, the flight-path an insect takes toward a light bulb, and many others.

Alphabet is also an abecedarian. Words beginning with A proliferate in the first section, B in the second, C in the third, and so on. At once an elegy for the world and an ode to the world, overtly concerned, thematically, with nuclear holocaust and ecological devastation, this incantatory poem employs many different kinds of repetitions. Some, like the alphabet letters, proceed in linear phases, shifting with each new point along the Pingala sequence; others, like the repeated verb “exists,” proliferate throughout the poem as a whole, from start to finish, across sections. This epistrophe (of “ . . . exists . . . exists”) creates a pervasive sonic reverberation and insistence throughout the long poem, as if existence itself is riding the spiral of the poem, encompassing more and more. In tandem with the steadily increasing, spiraling-outward length of the sections, these various repe- titions create the poem’s hypnotic, spell-binding effect.

Rather than encoding a spiral into its shape visually, or into its form mathematically, this third poem enacts a spiraling in its layering of image and memory, creating a cycle of returning and deepening that conjures a sense of spiraling downward, through one, central entry point. Like Christensen’s Alphabet, repetition plays a key role in enacting a spiralled motion, but here, the repetitions are more imagistic, sensory details that layer in texture and emotional complexity as they recur.

The Deer (from How to Be Drawn), by Terrance Hayes

Outside Pataskala I saw the deer with a soft white belly,

the deer with two eyes as blind as holes, I saw it leap

from a bush beside the highway as if a moment before

It leapt it had been a bush beside the highway, and saw

how if I wished it, I could be the deer, a creature bony

as a branch in spring, and when I closed my eyes, I found

the scent of muscadine, the berry my mother plucked

Sundays from the roadside where fumes toughened

its speckled skin and seeds slept suspended in a mucus

thick as the sleep of an embryo. It is the ugliest berry

along the road, but chewed it reminded me of speed,

and I saw when I was the deer that I didn’t have to be a deer,

I could become a machine with a woman inside it

moving at a speed that leaves a stain on the breeze

and on the muscadine’s flesh, which is almost meat,

the sweet pulp a muscadine leaves when it’s crushed

in the teeth of a deer, or a mother for that matter

or her child waiting with something like shame to be fed

a berry uglier than shame, though it is not like this

for the deer, it is not shame because the deer is not human,

it is only almost human when it looks on the road

and leaps covering at least thirty feet in a blink, the deer

I cannot be, the dumb deer, dumb and foolish enough

to ignore anything that runs but is not alive, a trafficking

machine filled with a distracted mind and body deadly

and durable enough to deconstruct a deer when it leaps,

I’m telling you, like someone being chased. I remember

a friend told me how, when he was eight or nine,

a half-naked woman ran to the car window crying her man

was after her with a knife, but his mother locked the doors

and sped away. Someone tell him his mother was not

a coward. That’s what he thinks. Tell him it was because

he and his little brother were in the car, she would not

let the troubled world inside. It was no one’s fault.

The mind separated from the body. I could almost see

the holes of her eyes, the white fuzz on her tongue,

the raised buds soft as a bed of pink seeds,

the hole of a mouth stretched wide enough to hold

a whole baby inside, I could almost see its eyes

at the back of her throat, I could definitely hear its cries.

I feel this poem digging downward with the spiralled trajectory of an auger drill. It begins, narratively and imagistically, in a place of utmost clarity and concreteness: We know exactly where we are (“Outside Pataskala . . . beside the highway”) and what we are looking at (a white-bellied deer leaping out from a bush). The poem grows more figurative, imaginative, and associative from there. The way Hayes returns to the instigating image, folding memory and sensory detail into it, contributes to a spiralled feeling of circling and tightening downward. Like Humienik’s “The Last Anchoress,” the sentence lengths in this poem, overall, move from long to short, beginning with two very long sentences, then a sentence of medium length, then a series of shorter sentences. That gradual, syntactical cinching in imbues the poem with the pull of a tightening vortex. When in the poem’s final movement, Hayes zooms in on the original, instigating image of the deer with extreme closeness, providing a meditation on close-up sensory details of the deer’s mouth, he carries us to what feels like the spiral’s inevitable end, that sharp, fine point where the so-called “opposites” explored in the poem—death and birth, human and deer—overlap, collapse, become one thing.

The spiral as a trajectory implies the existence of a focal point—a center, invisible and powerful, at which we arrive or from which we depart.

In general the spiral is a shape of both stillness and motion. Direction and evasion.

It can be helpful to think of the spiral as a symbol of obsession: an invitation to embrace returning—to one theme, scene, or figure—again and again, as compelled.

I hear from writers all the time that they want to escape themselves, to move beyond or away from the material that recurs in their work, but what if we stopped trying to escape? What if we spiralled, purposefully, into these subjects that have chosen us? I wonder what poems, what ouvres, we might leave the world then, if we surrendered to those personal bugaboos and gravitational pulls—if we approached them at the ultimate slant.

Two Accompanying Prompts

Outward-Spiral Prompt Inspired by the Quilts of Gee’s Bend & Organic Form

Begin with quotation—real or imagined—from a familial or literary elder (attributed). E.g. “My grandmother always used to say . . .” “Clifton once wrote . . .”

Describe a remembered image from a domestic space, using sensory detail. Incorporate at least two contrasting textures.

Respond to the quoted material from Step 1 in some way; argue with it, or apply it to something new; make the connection personal.

Describe the domestic space from Step 2—the larger space, around the image. Incorporate at least two (new) contrasting textures or colors in your sensory description.

Relay a specific social interaction between two people, in public.

Describe or otherwise conjure, briefly, the neighborhood or city where your domestic place is/was located, including at least one “landmark.”

Write a sentence that could be called “warm,” comforting, or reassuring.

Look back at what you’ve written for colors, mentioned or implicit. Include something different, here, that is also one of those colors. Have whatever it is move in some way: Describe it moving.

How would you describe the predominant tone of what you’ve generated so far? (Is it snarky, tender, plaintive, clinical, mournful, silly . . . ?). What tone might you consider to be that tone’s inverse or opposite? Try to step into that oppositional tone and describe an aspect of the landscape/ flora/ fauna in the region where your domestic space is located, using that new, contrasting tone.

Write “What I am really trying to say is ” and fill in the blank.

Now, delete “What I am trying to say is,” leaving only what you wrote to complete the thought.

Inward/Downward Spiral Prompt Inspired by Terrance Hayes’s “The Deer”

Set a timer. For 5 minutes: Search (literally, or in your memory) your own poem drafts for images or details that only occur one or two times, paying special attention to animals, plants, or other “natural” entities.

Choose one image/detail/object from Step 1 to serve as your draft’s primary, instigating image.

Begin drafting a poem that makes your chosen image your opening focus (the way the leaping deer is in the Terrance Hayes poem). Start by introducing the image in a plainly descriptive manner (no figurative language yet!) and place it, explicitly, in space and time).

You will now begin layering in the figurative (simile, metaphor). Describe your instigating image in a more strange and imaginative manner now, engaging at least two different senses (not just sight!).

Use the sensory description to leap, associatively, to a childhood memory.

Describe your central image again, this time in motion (if your image was already moving, initially, now make it move in a way it hasn’t yet moved). Engage, again, at least two different senses in your description. Don’t be afraid to get really weird.

Describe your instigating image now from a new perspective in place, in time, or both (e.g. from above, from very close up, as from a distant future . . . )

Leap now to relaying a longer memory or family story, one that haunts you or features prominently in your family lore, including something that was already mentioned in the first childhood memory you used; include sensory detail.

Look back at what you have. Aside from the repetition of your opening image, are any other repetitions of language naturally emerging in your draft? (Words, sounds, punctuation marks, verb tense . . . ). If so, include a slightly altered version of it now (think about how Terrance Hayes’s repeated phrase “I saw” becomes “I could almost see” at the end of his poem).

Acknowledge something you still cannot know, see, or understand about the instigating image.

CITATIONS

Christensen, Inger. Excerpt from Alphabet, translated from the Danish by Susanna Nied. Copyright © 1981, 2000 by Inger Christensen. Translation copyright © 2000 by Susanna Nied. Reprinted by permission of The Permissions Company, LLC, on behalf of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Hayes, Terrance. “The Deer” from How to Be Drawn, copyright © 2015 by Terrance Hayes. Reprinted by permission of Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Humienik, Patrycja. Excerpt from We Contain Landscapes. Copyright © 2024 by Patrycja Humienik. Reprinted by permission of Tin House.

Levertov, Denise. “Some Notes on Organic Form.” 1965. poetryfoundation.org

Moore, Marianne. “Art of Poetry No. 4.” The Paris Review. 1961. theparisreview.org

Gabrielle Bates is the author of Judas Goat (Tin House, 2023), named a Best Book of 2023 by NPR and Electric Lit.